Every trail has a story to tell and if you are patient enough you can learn to read the writing each footprint makes in the soft snow of winter. To practice reading tracks try this simple ac-tivity. Find an area of fresh snow. Ask your children to stand in a straight line with their backs to you. Make sure there is undisturbed snow behind them. Distract them by having them sing a song in unison. Now, behind your group’s backs, make a series of tracks. Here are some suggestions:

- Jump with two feet

- Walk on all fours Lay in the snow

- Walk normally then run Hop on one foot

- Turn around and walk backwards

When you have a clear track, have your group pivot in the same spot and study the story you’ve just made in the fresh snow. Can they tell you what happened? Here are some questions they can try to answer for any track they encounter. Use your tracking story as a guide.

- Which way was I going? Examine the scuff marks. Often a small and discernable scuff mark will appear at the rear of a track and can help to establish the direction of travel.

- How far apart are my tracks? Most animals have a “harmonic gate” – the normal speed at which they travel. When an animal runs, its stride (or the distance between tracks) increases.

- What was I doing? During the day, white-tailed deer will often rest at the side of a hill – the area where it has lain is called a bed.

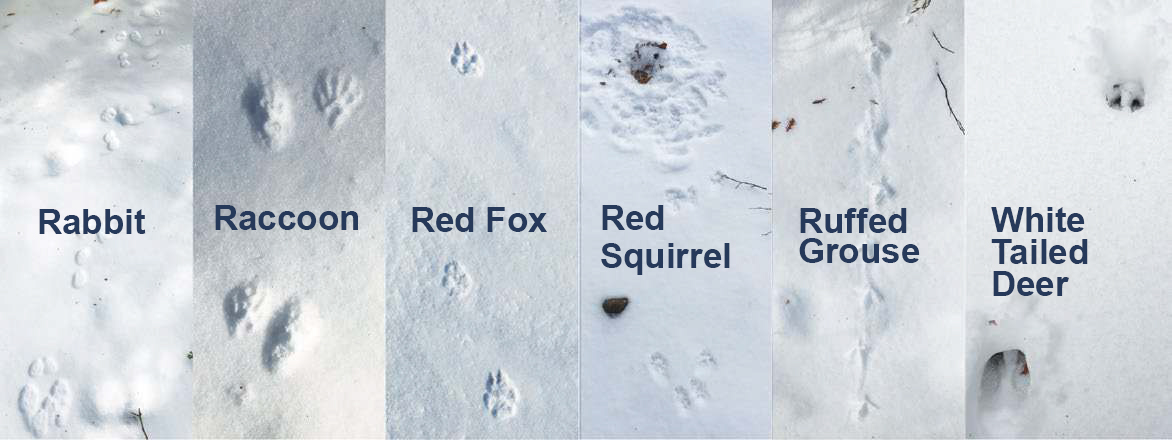

- What pattern do my tracks have? Rabbits hop with their two back legs beside each other and the front feet landing behind their back feet, one in front of the other. Raccoons often walk with their bigger rear foot beside their smaller front foot. Weasels, mink and members of the mustelid family bound. Deer, fox and coyotes walk in a fairly straight line.

After putting all the clues together, can you read the story of this track? This activity is an excellent way to begin the art of tracking. Go to a nearby forest, field or natural area. When you find tracks, follow them. Ask your children in which direction was the animal heading. Was it running, walking, lying down? Look for signs of browsing (rabbits have sharp teeth and nip small saplings at a 45-degree angle; deer don’t have any top teeth and they tend to tear and chomp overhanging branch-es and saplings; red squirrels husk cones, pull-ing off the scales in large piles called middens. Examine the pattern of the tracks to determine the animal which made them.

The more children follow tracks, the sharp-er their eyes become. Remember, tracks are more than just a few marks crisscrossing the landscape; they tell a fascinating tale. If you are lucky, you can follow tracks right to their source.