by jacob rodenburg with drew monkman

“Look what I found,” my son Liam yelled out in a lusty voice. “Come here quick!”

And so I did! Liam could barely contain his excitement as he bounced back and forth from one foot to the other. There, cradled in his cupped hands, was a red-backed salamander, its moist skin glistening in the sun.

“Is that ever cool!” proclaimed Liam, hanging on to his first-ever salamander for dear life.

This was a moment of deep connection, when little hands reached out and carressed a creature whose form has not changed for millions and millions of years. Liam touched something ancient that drew him in—that held him connected to the life forces that sustain and nurture us all.

It’s a moment that is all too rare for the average child. Kids today are spending more time indoors than any other generation. They spend ten times more time inside, in front of a TV or some kind of glowing screen, as they do playing and exploring outdoors. They can identify more than 100 corporate logos, but would be hard pressed to name just five native plant or animal species. Today’s children feel more comfortable in an air-conditioned mall than they do romping in a nearby woodland. Their parents do too.

If we want to raise the next generation of concerned stewards, we need to teach them to love, respect and know their own local natural environment—their own “neighbourwood.”

Erich Fromm first coined the term biophilia to describe the innate need that all children have to connect with other species; or as he describes it, the craving to be “attracted to all that is alive and vital.” In other words, children are born loving nature! It’s a desire that is deeply rooted in all of our genes. Edith Cobb, who wrote a wonderful book called The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood, argued that there is a window of time lasting from early childhood until about 14 years of age that if children are provided with rich and repeated experiences in nature, they are more likely to develop a life-long love and appreciation for the natural world. If we keep our children indoors however, we run the risk that nature may simply become the backdrop in front of which our children live out their daily lives, as inconsequential as the billboards, neon lights and telephone poles that decorate our cityscapes.

So, how can adults inspire a connection with nature in our children? Here are a few ideas!

Children are active, curious, energetic and enthusiastic. They love to play, imagine, discover and explore. It’s no wonder that a conventional hike through a familiar park or woods can become a boring pastime to a child. Take a few steps off the trail however and roll over a log or dip a butterfly net in a nearby pond, or romp through the edges of a rushing stream and the experience suddenly becomes an adventure!

• Take the time to explore with your child and go forth with explorer’s eyes. Be amazed at what you see, but also allow your children the gift of discovery. For example, you might know where there are salamanders along a certain trail. You could simply say to your children: “Hey…do you want to find a salamander?” Or you might say, “I wonder what we’ll find under these logs?” In the first instance, it is you who has owned the discovery. In the second, the excitement and joy belongs to the child. Remember to give children the time and space for discovery. Revealing a small hint of what is normally hidden from our sight is empowering, inspiring and at times, simply unforgettable.

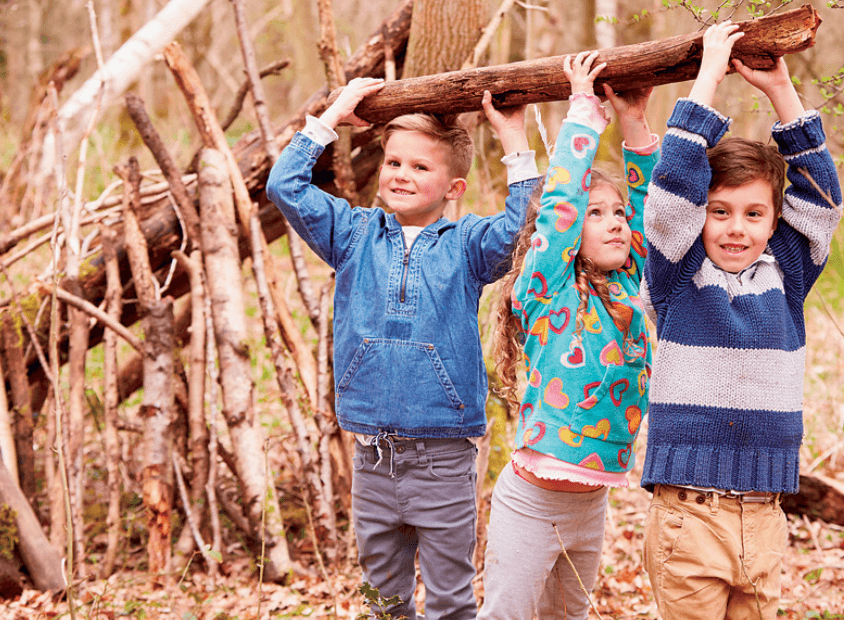

• One of my most memorable experiences of childhood was the time I took to build a fort or tree house. Children have a yearning to create dens, nests and hiding places. The process of building involves problem solving, understanding the properties of natural materials and lots of exercise! Together, build a survival debris hut.

• Create a collection table. Have your children display their discoveries—perhaps a collection of shells, feathers, plant material, living invertebrates, etc. that they find on their own. When they find something new, put something back from where it came. This way the table changes over time!

• We forget as adults how powerful language can be. Be careful how you speak about nature—whether we know it or not we often communicate values through our words and expressions. Seeing a spider may elicit the response of “Yuck—is that ever creepy!” Or finding a critter: “It’s dirty. You don’t know where it’s been.” If you want to cultivate a sense of wonder you need to use the language of wonder. “Wow, is that ever cool” or “Did you see that?”

• Huh? Consider the art of questioning. A question can either inspire curiosity or shut it down completely. Keep in mind that the engine of learning is curiosity. As adults, we need to remember that a name or a label is merely a beginning point. It’s the start of a story—an intriguing one—and it is up to you to keep the story going! A good question should invite other questions. Think of your questions as ways to encourage kids to ask why, wonder, and marvel at the natural world and to promote further exploration.

Characteristics of Kids and Nature: Ages and Stages

In our experience, we’ve found that children at different ages respond to nature in different ways. Use the hints below to help you think about how to approach nature with tots, teens and the in-be-tweens.

Younger Children: Ages 3 to 8

Nature Playscapes

The natural landscape lends itself to creative play. The space under the fragrant branches of spruce can magically transform into a castle or a spaceship. A fallen log morphs into a canoe or pirate ship. A stick can become a magic wand, sword or tent pole. It’s through unstructured play that children cultivate and enhance their imaginations. Being creative means creating! Let your children make forts, mud pies and flower crowns. Never doubt the value of exploring and playing in the natural environment. It’s these experiences that are at the very heart of developing young naturalists.

Connecting to the Land

Allow your child to forge a relationship with a small piece of land. It could be your backyard, a nearby green space or a local park. Go back to this same place over and over again and the land will become one of the touchstones of your child’s memory of home. Think of this connection as a relationship and just like any relationship, it requires commitment, time and effort. Visit frequently enough and for long enough that you’ll connect your child to something larger and deeper, until the very land itself becomes part of who they are. They’ll carry that with them for the rest of their lives.